- The Catcher In The Ryems. Scrolls Ela Classes For Beginners

- The Catcher In The Ryems. Scrolls Ela Classes List

Now unscowl your faces, good people. Objections noted. In fact, I had more trouble deciding if Catcher in the Rye belonged in Practical Classics than any other book.Catcher, it seems, belongs to a small group of high school classics with a built-in self-destruct button.No one reads Atlas Shrugged past age twenty-five unless they voted for the Objectivist candidate in the last election. The Catcher in the Rye 128-page novel unit includes student coursework, activities, quizzes, tests, and more aligned with the ELA Common Core State Standards for tenth through twelfth grade. Designed for as much or as little teacher instruction or intervention as you desire, students will be able to. Today's Learning Target: Students will create contexts for The Catcher in the Rye's setting—specifically the cultural values and societal expectations of the upper middle class in the 1950s. Students will strengthen understanding of rebellion and conformity within the novel’s time period. This course helps you review the characters and events of 'The Catcher in the Rye' using a simple and fun video format. These lessons refresh your memory of important topics while interactive.

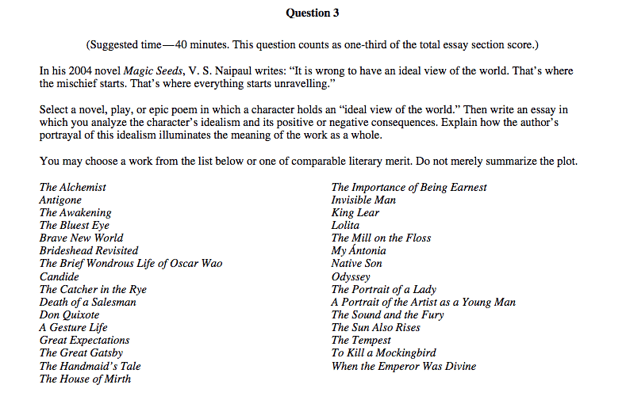

One of the most widely taught novels in the United States, J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951) opens with the sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield’s disillusioned departure from what may be the last in a series of schools that have failed to inspire, nurture, or support him, followed by a painful, sleep-deprived odyssey through the streets of New York City. The readiness of teachers to embrace and assign this novel, despite its implicit indictment of the American educational system, is evidence of its extraordinary capacity to appeal even to those whom it risks insulting. Just about everyone Holden encounters, including his teachers, his classmates, his friends, and his fellow New Yorkers, is a “phony,” behaving in accordance with artificial conventions and disguising self-interest underneath a veneer of amiability. Yet the novel promotes solidarity with the protagonist, and one can imagine countless readers concluding: yes, the world is awash in materialism, shallowness, and insincerity, but I, like Holden, am different. Since 1951 when it was first published, The Catcher in the Rye has served as a resonant expression of alienation for several generations of adolescent readers and adults who have considered themselves at odds with the norms and institutions of American society.

Salinger follows a long tradition of quixotic individualism among American authors—many of whom treat society as inherently corrupt and corrupting. The character to whom critics have most frequently compared Holden Caulfield is Huck Finn. Like Huck, Holden is both precocious and naïve, a worldly trickster quick to lie to protect himself, but preternaturally sensitive and thus horrified by the cruelty and decadence that he witnesses. Both characters pursue an enclave of freedom and innocence and both resist the efforts of adults to educate and mold them in accordance with prevailing standards of conduct. They assert their own relatively untarnished status through a vernacular style that does not conform to standard English. In moments, Salinger seems to explicitly acknowledge Twain’s influence, as a juxtaposition of two short passages demonstrates. Huck: “Then I set down in a chair by the window and tried to think of something cheerful, but it warn’t no use. I felt so lonesome I most wished I was dead.” Holden: “All I did was, I got up and went over and looked out the window. I felt so lonesome, all of a sudden. I almost wished I was dead.” Both boys are motivated to consider suicide by a feeling of intense loneliness. This suggests that Huck and Holden not only wish to escape the constricting, corrupting influence of civilization as they perceive it, but also to discover some unprecedented form of community or intimacy that the prevailing social order has denied them.

While the still-pervasive ethos of individualism in the United States is in part responsible for The Catcher in the Rye’s persistent popularity, it is also important to understand the text in relation to its immediate historical context: the 1950s. According to many historians and critics, this moment was characterized by a culture of consensus. The postwar economy was prospering, and millions of Americans bought homes in the newly developed suburbs. Assisted by the GI Bill, veterans attended college in record numbers, thus expanding the ranks of the professional-managerial class. The political unrest fostered by the Great Depression had subsided and, faced with the vision of Stalin’s nightmarish totalitarian regime, radical dissent lost its appeal. Many Americans, most notably many writers and intellectuals, saw the need to defend the United States and the freedoms that it purportedly protected against the communist threat. At the same time, however, critics were concerned by patterns of widespread conformity. Mass market commodities, bewildering corporate bureaucracies, and uniformly designed suburbs, they feared, were serving to homogenize the population, creating what sociologist David Riesman in 1950 described as “the other-directed” person, or what journalist William Whyte six years later termed the “organization man”—individuals focused on getting along, desperate for the approval of others, and incapable of independent thought or action. Holden Caulfield famously offered his own term of disparagement, “phony,” and thus appealed to broadly shared anxieties about a conformist culture.

Recently, scholars have challenged the characterization of the 1950s as a period of uniformity, optimism, and harmony, pointing to unspoken divisions, festering conflicts, and subterranean forms of dissatisfaction and revolt. While many WWII soldiers gladly reintegrated into American society, many others suffered from psychic scars. Mental health clinics proliferated during this period in response to a variety of psychological complaints among veterans and the general population. Subcultures formed around the abuse of illicit drugs. Millions of Americans, as Alfred Kinsey discovered, secretly engaged in a variety of sexual practices considered deviant. Racial tensions escalated, leading to the growth of the Civil Rights Movement as well as the emergence of the Nation of Islam as an outlet for black frustrations. And if the Cold War promoted patriotism, the threat of worldwide annihilation fostered diffuse anxiety, and the immediate postwar period witnessed the formation of pacifist groups committed to civil disobedience. While most Americans did not actively engage in political demonstrations during this time, for those who were not entirely satisfied with the lifestyles available to them, for those whose experiences clashed with the picture of a self-confident, optimistic America, for those who found the society that they inhabited artificial or shallow, Holden Caulfield served as a misfit hero.

Since its publication, The Catcher in the Rye has been banned frequently in schools and libraries across the country and, while civic crusaders have pointed to its obscene language, Holden’s frank discussion of unsettling and taboo subjects incompatible with America’s positive self-image also provoked concerns. He describes the sexual promiscuity of his classmates and the profound ambivalence that this inspires in him, detailing his awkward encounter with a prostitute and his eventual refusal of her services. “Sex,” he remarks, “is something I just don’t understand. I swear to God I don’t.” He also discusses his struggles with mental illness: “I’ll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy.” The narrative suggests that in addition to his distant and neurotic parents, an inhospitable environment—a vicious prep school social hierarchy, callous teachers, and a city of predators, strangers, and social-climbers—precipitates his breakdown. Holden offers an unflattering picture of postwar America and adopts a series of unorthodox positions at odds with mainstream values, calling himself “sort of an atheist” and “a pacifist.” He asserts, “I’m sort of glad they’ve got the atomic bomb invented. If there’s ever another war, I’m going to sit right the hell on top of it”—a remark that aligns the United States’ military strategy with the suicidal impulses of a confused adolescent.

Above all else, Holden resists the imperative to grow up and assume adult responsibilities, which would be to surrender his integrity. His older brother D. B., who works as a Hollywood writer, has, he claims, become a “prostitute.” Unable to think of a single profession that he would like to enter, Holden declares in response to his younger sister Phoebe’s suggestion that he become a lawyer:

I mean they’re all right if they go around saving innocent guys’ lives all the time, and like that, but you don’t do that kind of stuff if you’re a lawyer. All you do is make a lot of dough and play golf and play bridge and buy cars and drink Martinis and look like a hot-shot. And besides. Even if you did go around saving guys’ lives and all, how would you know if you did it because you really wanted to save guys’ lives, or because you did it because what you really wanted to do was be a terrific lawyer, with everybody slapping you on the back and congratulating you in court when the goddam trial was over, the reporters and everybody, the way it is in the dirty movies? How would you know you weren’t being a phony? The trouble is, you wouldn’t.

The rituals, rules, and rewards that attend adult professional life are so insidious, according to Holden, that they forestall even the capacity to recognize one’s own hypocrisy or to distinguish sincerity from self-deception. Rejecting the legal profession, Holden describes his ideal vocation in the most famous passage in the book:

I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be.

Holden’s urge to shield children from danger and allow them to play endlessly exemplifies his desire to suspend time, to inhabit a space of youth preserved indefinitely, a desire he also reveals through his adoration of the ten-year-old Phoebe and his attachment to the Natural History Museum, where “everything always stayed right where it was.”

Paradoxically, the museum exhibits its subjects in an immobilized state, thus impeding their temporal development only by imposing upon them a static, deathly condition. Holden’s refusal of adulthood, to put it another way, coincides with his suicidal tendencies, and many readers have argued that his critique offers no alternative to the phony society that he deplores, other than infantilism, insanity, or death. Indeed The Catcher in the Rye, some claim, irresponsibly celebrates immaturity, encouraging its readers to remain children and thereby to resist practical engagement with the social problems that the book diagnoses. One might contend, however, that Holden’s stubbornly childlike perspective demonstrates greater wisdom and maturity than the ostensibly more realistic outlook of those who gladly accept the conventional roles offered to them. Though admitting that, “some times I act like I’m about thirteen,” Holden maintains, “sometimes I act a lot older than I am—I really do—but people never notice it. People never notice anything.” A central challenge of reading The Catcher in the Rye, arguably, is learning to detect in Holden’s seemingly simple, naive voice, a measure of perceptiveness and subtlety that the jaded, pseudo-sophisticated adults who urge him to “play according to the rules” utterly lack. Of course one can reach this understanding without concluding that Holden represents a viable model for how to live, especially given the pain and insecurity that his heightened sensitivity produces. According to critic Leerom Medovoi, Salinger’s novel allows readers to identify with the radical idealism that Holden exemplifies and at the same time to position this stance safely within the phase of exploratory adolescence, thus treating it as something that one must ultimately outgrow.

Holden never seems to find the community of fellow idealists that he seeks, but he invites readers to share his sensibility, often addressing them directly, asserting in remembering his deceased older brother that “you’d have liked him,” or in describing a self-indulgent piano player, “you would’ve puked.” For many youths, reading The Catcher in the Rye functioned in the 1950s as a badge of self-declared authenticity, and some critics hold that it helped to foster forms of disaffection central to the counter-cultural movement of the 1960s. Its power to provoke identification and compassion among readers even now testifies to the persistence of social pressures and expectations that make adolescence an especially bewildering and painful time. For those who read his novel at the right moment, Salinger’s not inconsequential gift is to render this difficult period of life at least slightly more bearable.

Timothy Aubry is an assistant professor of English at Baruch College, The City University of New York.

Works Cited

Kinsey, Alfred. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1948.

Kinsey, Alfred. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1953.

Medovoi, Leerom. “Democracy, Capitalism, and American Literature: The Cold War Construction of J. D. Salinger’s Paperback Hero.” The Other Fifties: Interrogating Midcentury American Icons. Ed. Joel Foreman. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Riesman, David, et al. The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950.

Salinger, J. D. The Catcher in the Rye. Boston: Little, Brown, 1951.

Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. 1885; reprint, New York: Random House, 1996.

Whyte, William. The Organization Man. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956.

1

Talking Like Holden

Kind of Activity:

Group Work

Objective:

To understand how Holden's diction is unique and reveals his character

Common Core Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.L.5 ; CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.L.3

The Catcher In The Ryems. Scrolls Ela Classes For Beginners

Structure:

The Catcher In The Ryems. Scrolls Ela Classes List

Choose a passage and have students analyze Holden's word choices and sentence constructions in that particular passage, to create a picture of his speech and what it reveals about his character. Unique speech patterns include: use of the passive voice; use of the second person ('you' instead of 'I'); repeated phrases and words (phony, 'it killed me,' 'listen,' 'crumby,' 'I sort of did X,'...